www.aljazeerah.info

Opinion Editorials, March 2017

Archives

Mission & Name

Conflict Terminology

Editorials

Gaza Holocaust

Gulf War

Isdood

Islam

News

News Photos

Opinion Editorials

US Foreign Policy (Dr. El-Najjar's Articles)

www.aljazeerah.info

|

Oil Majors' Costs Have Risen 66% Since 2011 By Nick Cunningham Oil Price, Al-Jazeerah, CCUN, March , 2017 |

|

|

|

|

The oil majors reported

poor earnings for the fourth quarter of last year, but many oil

executives struck an optimistic tone about the road ahead. Oil prices have

stabilized and the cost cutting measures implemented over the past three

years should allow companies to turn a profit even though crude trades for

about half of what it did back in 2014.

The collapse of oil prices

forced the majors to slash spending on exploration, cut employees, defer

projects, and look for efficiencies. That allowed them to successfully

lower their breakeven price for oil projects. However, some of that could

be temporary, with oilfield services companies now

demanding higher prices for equipment and drilling jobs, in some cases

upping prices by as much as 20 percent. The result could be an uptick in

the cost of producing oil for the first time in a few years. Rystad Energy

estimated the average shale project could see costs rise by $1.60 per

barrel, rising to $36.50.

That does not seem like the end of the

world. After all, those breakeven prices are still dramatically lower than

what they were back in 2014. In fact, Reuters put together a

series of charts depicting the fall in costs for shale production in

different parts of the United States. Every major shale basin – the Eagle

Ford, the Bakken, the Niobrara, and the Midland and Delaware basins in the

Permian – have seen breakeven prices fall by as much as half since 2013.

The slight uptick in costs expected in 2017 is a rounding error compared

to the reductions over the past half-decade.

But that is just for

shale drilling. The oil majors produce most of their oil outside of the

shale patch, with much of their output coming from longer-lived projects

in deepwater, for example. To be sure, some of the largest oil companies

have made some progress in cutting costs over the past few years, but a

new report casts doubt on the industry’s track record.

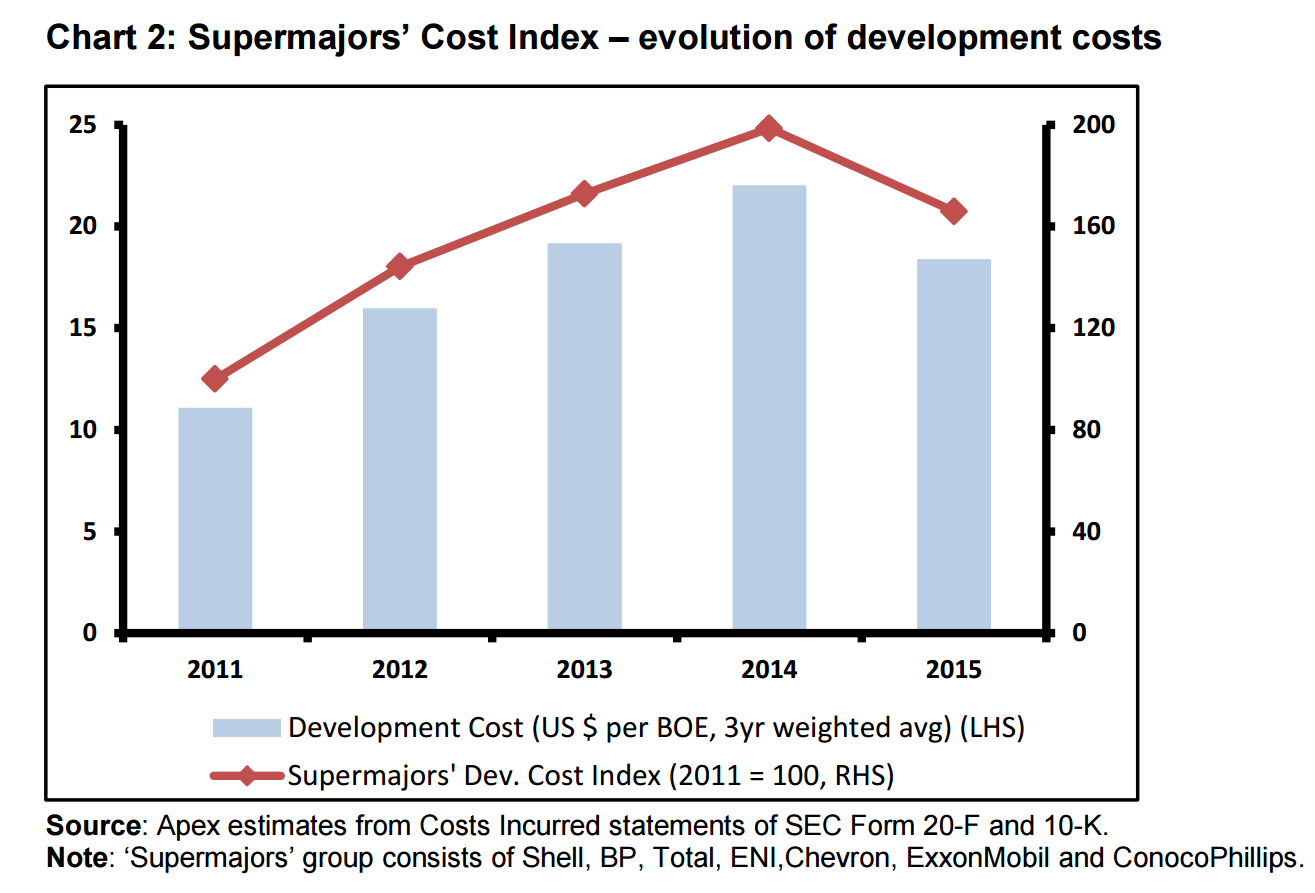

According

to new research from

Apex Consulting

Ltd., the oil majors are still spending more to develop a barrel of

oil equivalent than they were before the downturn in prices – in fact,

much more. Apex put together a proprietary index that measures cost

pressure for the “supermajors” – ExxonMobil, Royal Dutch Shell, Chevron,

Eni, Total and ConocoPhillips. Dubbed the “Supermajors’ Cost Index,” Apex

concludes that the supermajors spent 66 percent more on development costs

in 2015 than they did in 2011, despite the widely-touted “efficiency

gains” implemented during the worst of the market slump. It is important

to note that this measures “development costs,” and not exploration or

operational costs.

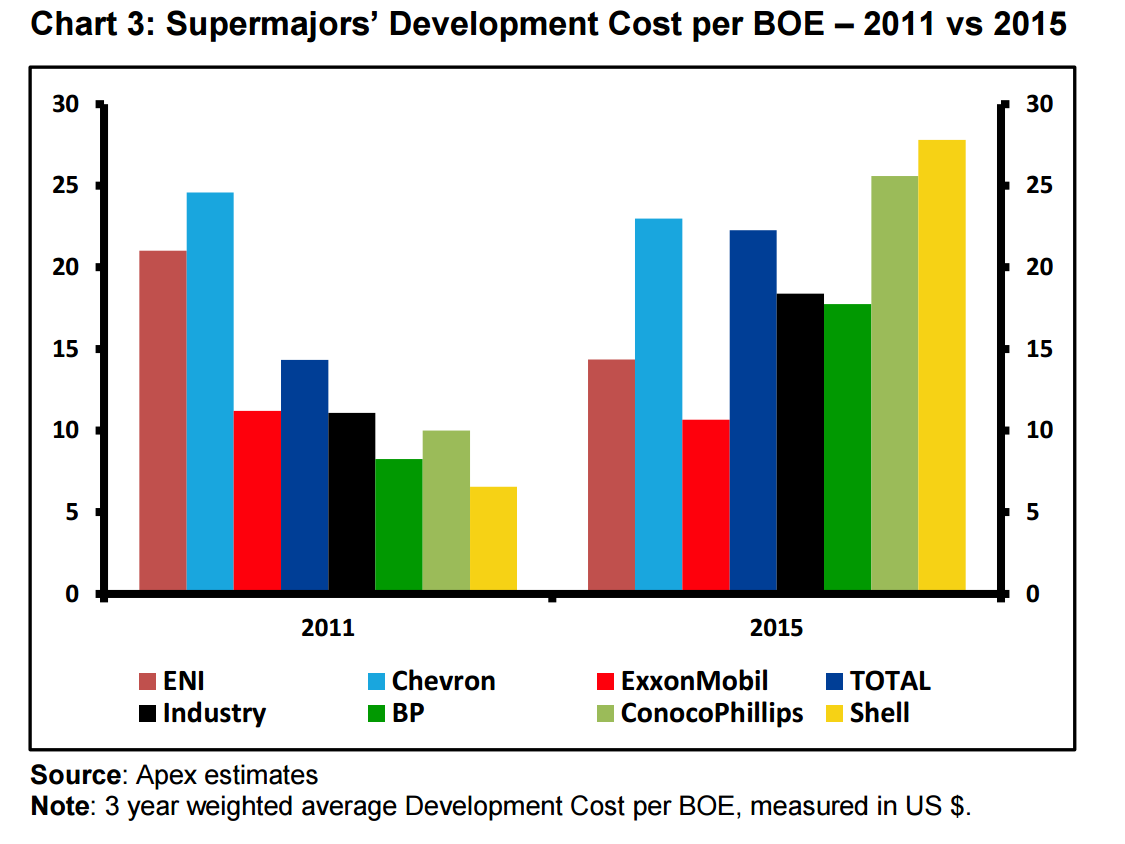

However, performances varied by company. Eni,

for example, saw its development costs decline by 32 percent between 2011

and 2015, a notable achievement. Chevron and ExxonMobil also posted

efficiency gains, although more modest figures than Eni. Chevron’s costs

fell 6 percent and Exxon’s were down 5 percent over the five-year period.

At the other end of the spectrum is Royal Dutch Shell, which saw

development costs quadruple. ConocoPhillips and BP fared only slightly

better, with costs roughly doubling over the timeframe. As a whole, the

development costs for the group of “supermajors” rose 66 percent to $18.39

per barrel.

After the collapse of oil prices in 2014, the cost

index did decline. Oil producers squeezed their suppliers, streamlined

operations, and improved drilling techniques. But costs still stood 66

percent higher than in 2011.

The index points to underlying

structural increases in development costs for the broader industry.

At $18 per barrel, the cost figure would seem rather low. But it is

important to note that this is just for “development costs,” which

represent just over half of a company’s total cost. That figure excludes

the cost of exploration as well as funding ongoing operations. So the

“breakeven price” so often quoted in the media is actually quite a bit

higher. BP, for example, recently

admitted that its finances will not breakeven unless oil trades at

roughly $60 per barrel.

The supermajors are in a tricky position.

They are trying to cut back on spending in order to fix their finances and

pay down the massive pile of debt that they have accumulated in the past

few years. However, their reserves will decline if they fail to replace

them. Exxon, for example, only replaced 67 percent of the oil it produced

in 2015.

Moreover, as Apex Consulting notes, oilfield services

might demand higher prices in the future as drilling activity picks up.

Right now, offshore rigs are still underutilized, meaning that price

inflation has yet to kick in.

In other words, the decline in costs

post-2014 are, at least in part, cyclical. Costs will rise again as

activity picks up unless oil producers work with their suppliers to

address the underlying structural costs of oil production.

Link to

original article:

http://oilprice.com/Energy/Energy-General/Oil-Majors-Costs-Have-Risen-66-Since-2011.html

***

Next Oil Rally? Futures Say Market Is Tightening

By Nick Cunningham

U.S. oil inventories are at record levels, but

there are a few glimmers of hope that the glut could be starting to subside.

Storing crude oil for sale at a later date is no longer profitable,

as the futures curve has flattened out in recent weeks, depriving traders of

a strategy that has served them well over the past few years. The market “contango,”

in which front-month oil contracts trade at a discount to oil futures six

months or a year out, has all but vanished. The differential must be large

enough to cover the cost of storage, and for many time spreads that is no

longer the case. After three years of a steep contango, storing oil simply

to take advantage of the time spreads is increasingly uneconomical.

One of the more expensive forms of storage is floating on tankers at sea,

and because of the narrowing contango, floating storage is unprofitable

today. Reuters reports that traders are beginning to unload crude from

floating storage along the Gulf Coast. "Right now, traders aren't

incentivized (to store)," Sandy Fielden, director of oil and products

research at Morningstar, told

Reuters in an interview. "It won't all stampede out of the gate, but

inventory levels will come down. What will happen is that some of it will go

to refineries, but a fair amount will be exported too."

Just as the

rapid rise of floating storage in 2015 and 2016 was a sign of the deepening

global supply imbalance, draining tankers of stored oil is an early sign

that the supply glut is receding.

So far, it is only the most

expensive storage facilities that are seeing drawdowns – the U.S. on the

whole has seen crude stocks swell to

record highs. But oil analysts argue that the surge in crude inventories

is a symptom of stepped up imports booked at the end of 2016, when OPEC

members pumped out huge volumes of crude just ahead of implementation of

their deal to cut production. After a few weeks of transit time, the extra

supply started showing up in U.S. storage data in January and February. In

other words, the stock builds could be a temporary anomaly.

More

recently, the time spreads for Brent futures also indicate increasing

tightness in the market. John Kemp of Reuters

notes

that the spread between futures between April and May has sharply narrowed

this month, meaning that the market is betting on a supply deficit as we

move into the second quarter. The spreads for May-June and June-July are

even smaller, trading at a few cents per barrel. This is a complicated way

of saying that there isn’t a way to make money by buying oil, paying for

storage, and selling it at a later date.

In a separate report,

Reuters notes that inventories are also starting to

drawdown in Asia, adding further evidence that the glut is not as bad as

feared. As OPEC has throttled back on production, Asia is starting to see

the impact. Reuters says that unusually large drawdowns took place across

key oil hubs in Asia – 6.8 million barrels of oil were withdrawn from tanker

storage off of Malaysia’s coast while Singapore saw a 4.1 million barrel

decline and Indonesia’s storage fell by 1.2 million barrels.

"Dancing contango is now not a profitable thing to do, so we've sold out,"

an oil trading manager told Reuters. The trader no longer stores oil on

tankers because of the disappearing contango.

The details of the

contango and the oil futures market may seem complex and arcane, but the

shift in time spreads is exactly what OPEC has been targeting with its

supply cut. By cutting near-term supply, OPEC has succeeded in changing the

economics of oil trading, forcing inventories to draw down. That could cause

a short-term supply problem as oil is unloaded from storage, but in the long

run OPEC needs to drain that excess supply from storage tanks around the

world in order to spark higher prices.

Traders are more and more

confident that the oil market will experience tighter conditions as we move

into the second quarter, a bet that is reflected in both the time spreads

and the exceptional buildup in

bullish

positions on crude oil. The oil price rally is not without its

risks – very notable risks that have been

covered in

previous

articles – but for now, the futures market is offering investors and

traders some reasons for bullishness.

Link to original article:

http://oilprice.com/Energy/Energy-General/Next-Oil-Rally-Futures-Say-Market-is-Tightening.html

Share the link of this article with your facebook friends

|

|

|

|

||

|

||||||