www.aljazeerah.info

Opinion Editorials, September 2012

Archives

Mission & Name

Conflict Terminology

Editorials

Gaza Holocaust

Gulf War

Isdood

Islam

News

News Photos

Opinion Editorials

US Foreign Policy (Dr. El-Najjar's Articles)

www.aljazeerah.info

The Myth That Japan Is Broke:

Al-Jazeerah, CCUN, September 8, 2012

Japan’s massive government debt conceals massive benefits for the Japanese

people, with lessons for the U.S. debt “crisis.”

In an April 2012 article in Forbes titled “If

Japan Is Broke, How Is It Bailing Out Europe?”, Eamonn Fingleton pointed

out

the Japanese government was by far the largest single non-eurozone

contributor to the latest Euro rescue effort.

This, he said, is “the same government that has been going round

pretending to be bankrupt (or at least offering no serious rebuttal when

benighted American and British commentators portray Japanese public finances

as a trainwreck).” Noting that

it was also Japan that rescued the IMF system virtually single-handedly at

the height of the global panic in 2009, Fingleton asked:

How can a nation whose government is supposedly the most

overborrowed in the advanced world afford such generosity? . . .

The betting is that Japan’s true public finances are far

stronger than the Western press has been led to believe. What is undeniable

is that the Japanese Ministry of Finance is one of the most opaque in the

world . . . .

Fingleton acknowledged that the Japanese government’s

liabilities are large, but said we also need to look at the asset side of

the balance sheet:

[T]he Tokyo Finance Ministry is increasingly borrowing

from the Japanese public not to finance out-of-control government spending

at home but rather abroad. Besides stepping up to the plate to keep the IMF

in business, Tokyo has long been the lender of last resort to both the

U.S. and British governments. Meanwhile it borrows 10-year money at an

interest rate of just 1.0 percent, the second lowest rate of any borrower in

the world after the government of Switzerland.

It’s a good deal for the Japanese

government: it can borrow 10-year money at 1 percent and lend it to the U.S.

at 1.6 percent (the going rate on

U.S. 10-year bonds),

making a tidy spread.

Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio is nearly 230%,

the worst of any major country in the world.

Yet

Japan

remains the world’s largest

creditor country,

with net foreign assets of $3.19 trillion.

In 2010, its GDP per capita

was more than that of France, Germany, the U.K. and Italy.

And while China’s economy is now larger than

Japan’s because of its burgeoning population (1.3 billion versus 128

million), China’s $5,414 GDP per capita is only 12 percent of Japan’s

$45,920.

How to explain these

anomalies?

Fully 95 percent of Japan’s national debt

is held domestically by the Japanese themselves.

Over 20% of the debt is

held by Japan Post Bank, the Bank of Japan, and other government entities.

Japan Post is the

largest holder of domestic savings in the world, and it returns interest to

its Japanese customers.

Although theoretically privatized in 2007, it

has been a political football, and 100% of its stock is still owned by the

government.

The Bank of Japan is 55% government-owned and

100% government-controlled.

Of the remaining debt, over

60% is held by

Japanese banks, insurance companies and pension funds.

Another chunk is held by individual Japanese savers.

Only 5% is held by

foreigners, mostly central banks.

As noted in a September 2011

article in The New York Times:

The Japanese government is in deep debt, but the rest of Japan has ample

money to spare.

The Japanese government’s debt

is

the people’s money.

They own each other, and they collectively

reap the benefits.

Myths of the Japanese Debt-to-GDP Ratio

Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio looks

bad.

But

as economist Hazel Henderson notes,

this is just a matter of accounting practice—a practice that she and other

experts contend is misleading.

Japan leads globally in most areas of

high-tech manufacturing, including aerospace.

The debt on the other side of its balance

sheet represents the payoffs from all this productivity to the Japanese

people.

According to Gary Shilling,

writing on

Bloomberg in June

2012, more than half of Japanese public spending goes for debt service and

social security payments.

Debt

service is paid as interest to Japanese “savers.”

Social security and interest on the national

debt are not included in GDP, but these are actually the social safety net

and public dividends of a highly productive economy.

These, more than the military weapons and

“financial products” that compose a major portion of U.S. GDP, are the real

fruits of a nation’s industry.

For Japan, they represent the enjoyment by the

people of the enormous output of their high-tech industrial base.

Shilling writes:

Government

deficits are supposed to stimulate the economy, yet the composition of

Japanese public spending isn’t particularly helpful. Debt service and

social-security payments -- generally non-stimulative -- are expected to

consume 53.5 percent of total outlays for 2012 . . . .

So says conventional theory, but

social security and interest paid to domestic savers actually do stimulate

the economy.

They do it by getting money into the pockets

of the people, increasing “demand.”

Consumers with money to spend then fill the

shopping malls, increasing orders for more products, driving up

manufacturing and employment.

Myths About Quantitative Easing

Some of the money for these

government expenditures has come directly from “money printing” by the

central bank, also known as “quantitative easing.”

For over a decade, the Bank of Japan has been

engaged in this practice; yet the hyperinflation that deficit hawks said it

would trigger has not occurred.

To the contrary, as noted by

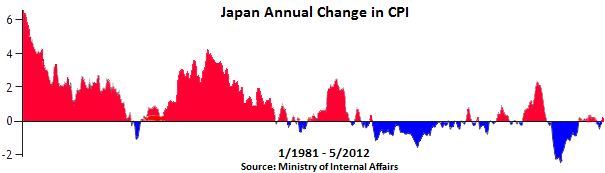

Wolf Richter in a May 9, 2012 article:

[T]he Japanese [are] in fact among the few people in the

world enjoying actual price stability, with interchanging periods of minor

inflation and minor deflation—as opposed to the 27% inflation per decade

that the Fed has conjured up and continues to call, moronically, “price

stability.”

He cites as evidence the following graph from the

Japanese Ministry of Internal Affairs:

How

is that possible?

It all depends on where the money generated by

quantitative easing ends up.

In Japan, the money borrowed by the government

has found its way back into the pockets of the Japanese people in the form

of social security and interest on their savings.

Money in consumer bank accounts stimulates

demand, stimulating the production of goods and services, increasing supply;

and when supply and demand rise together, prices remain stable.

Myths About

the “Lost Decade”

Japan’s finances have long been shrouded in secrecy, perhaps because when

the country was more open about printing money and using it to support its

industries, it got

embroiled in World War II.

In his

2008 book

In the Jaws of the Dragon,

Fingleton suggests that Japan feigned insolvency in the “lost decade” of the

1990s to avoid drawing the ire of protectionist Americans for its booming

export trade in automobiles and other products.

Belying the weak reported statistics, Japanese

exports increased by 73% during that decade, foreign assets increased, and

electricity use increased by 30%, a tell-tale indicator of a flourishing

industrial sector.

By 2006, Japan’s exports were three times what

they were in 1989.

The

Japanese government has maintained the façade of complying with

international banking regulations by “borrowing” money rather than

“printing” it outright.

But borrowing money issued by the government’s

own central bank is the functional equivalent of the government printing it,

particularly when the debt is just carried on the books and never paid back.

Implications

for the “Fiscal Cliff”

All

of this has implications for Americans concerned with an out-of-control

national debt.

Properly managed and directed, it seems, the

debt need be nothing to fear.

Like Japan, and unlike Greece and other

Eurozone countries, the U.S. is the sovereign issuer of its own currency.

If it wished, Congress could fund its budget

without resorting to foreign creditors or private banks.

It could do this either by issuing the money

directly or by borrowing from its own central bank, effectively

interest-free, since the Fed rebates its profits to the government after

deducting its costs.

A little quantitative easing can be a good thing, if the money winds up with

the government and the people rather than simply in the reserve accounts of

banks. The national debt can

also be a good thing.

As Federal Reserve Board

Chairman Marriner

Eccles testified in hearings before the House Committee on Banking and

Currency in 1941, government credit (or debt) “is what our money system is.

If there were no debts in our money system, there wouldn’t be any

money.”

Properly directed, the national debt becomes the spending money of the

people.

It stimulates demand, stimulating productivity.

To keep the system stable and sustainable, the

money just needs to come from the nation’s own government and its own

people, and needs to return to the government and people.

_______________________

Ellen

Brown is an attorney and president of the Public Banking Institute,

http://PublicBankingInstitute.org.

In Web of Debt, her latest of eleven books, she shows how a

private cartel has usurped the power to create money from the people

themselves, and how we the people can get it back. Her websites are

http://WebofDebt.com and

http://EllenBrown.com.

|

|

|

|

||

|

||||||