www.aljazeerah.info

News, November 2017

Archives

Mission & Name

Conflict Terminology

Editorials

Gaza Holocaust

Gulf War

Isdood

Islam

News

News Photos

Opinion Editorials

US Foreign Policy (Dr. El-Najjar's Articles)

www.aljazeerah.info

|

Editorial Note: The following news reports are summaries from original sources. They may also include corrections of Arabic names and political terminology. Comments are in parentheses. |

Game for the Wealthy:

The Ongoing Battle Against Tax Havens Around the World

DER SPIEGEL, November 10, 2017

|

|

| The Paradise Papers have directed unwanted attention to companies like Apple and Nike. |

Game for the Wealthy: The Ongoing Battle against Tax Havens

The Paradise Papers offer only the most recent look into the widespread practice of tax avoidance. Governments around the world have taken steps recently to block such strategies, but it is unclear whether they will ultimately be successful.

Early this week, the financial world was rocked by the latest revelations about tax tricks used around the world by corporations and the super-rich. The leaks, which included 13.4 million documents and were labeled the "Paradise Papers," were the product of an international investigative consortium including journalists from influential German daily Süddeutsche Zeitung.

The cases uncovered are similar to those revealed in the previous leak, the Panama Papers, which triggered global outrage last year. The data describes how the rich and super-rich, international stars and companies try to avoid paying taxes in their home countries. It is a game for the wealthy.

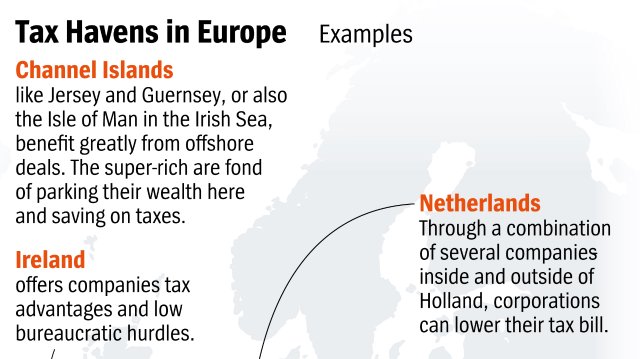

The players are usually multinational corporations seeking to shrink their tax bill using convoluted structures. Tech-giant Apple once again stands accused of skullduggery, as does sporting-goods producer Nike. The accomplices are also largely the same. The deals in question invariably involve tax havens such as the Bermuda Islands, British dependencies such as the Isle of Man or Jersey, and European member states like the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Ireland.

The questions facing politicians are also the same ones that come up after every new substantial leak: How can we continue to tolerate a situation in which tax loopholes still haven't been closed? And why are EU member states still allowed to cheat their partners within the bloc out of tax revenues?

Indignation is understandable, though out of date on many points. Many of the tax avoidance strategies wouldn't work today because numerous countries have joined forces to eliminate tax loopholes. The malfeasance uncovered by the Panama and Paradise Papers is sometimes akin to looking in the rearview mirror.

But it is also true that closing all of the loopholes that exist is an arduous, sometimes frustrating political process, with the economic interests of the countries involved far too divergent to ensure universal satisfaction. There are, though, several positive developments. Cooperation between the fiscal authorities of dozens of countries is now taking place on multiple levels. For example, the largest industrialized and developing countries are working together within the framework of the G-20 on the so-called "base erosion and profit shifting" (BEPS) initiative. Participating countries are no longer allowed to wait until they are asked, but must automatically provide fiscal information to participating partners. The regulation has been in force since September, with 50 countries having already joined and 50 others planning to do so.

Hurdles to Profit Shifting

International agreements will also supposedly make it more difficult for companies to shift profits from one country to another in an effort to pay the lowest tax rate possible. The most popular vehicle for doing so among multinationals is charging inflated "management fees" and brand licensing fees among susidiaries.

An international register has also been introduced to publicize the owners of companies, including those that participate in tax-saving models. That creates transparency, though it doesn't go quite far enough for German Chancellor Angela Merkel's outgoing administration. Berlin had initially wanted to list all companies and individuals who profited from the structures. But the proposal for such an expanded register was blocked by Britain and the Netherlands. Erstwhile German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble and his allies from other EU member states could do nothing since tax issues must be passed unanimously in the bloc.

That also explains why there is no universal minimum corporate tax rate in the EU, an absurdity given that such minimum rates have been agreed on in Europe for tobacco taxes and VAT. In both cases, the taxes levied by EU member states may not fall below a predetermined level. But countries like Malta, for example, prevent the introduction of a minimum corporate tax rate in Europe.

The Mediterranean country is also known for trying to lure the owners of smaller companies to set up shop on the island. If they do so, earnings up to 5 million euros per year are only taxed at a rate of 15 percent. Anything above that is tax free.

Those opposed to tax avoidance measures only managed to close one tiny loophole. Recently, an informal minimum tax rate was applied to so-called license boxes. That model involves the separate declaration of income from patents, income which is then taxed at a lower rate. In Ireland and the Netherlands, such income is taxed at half the normal corporate rate. The problem, though, is that EU law is silent about what the minimum corporate tax rate should be.

An additional transparency initiative has thus far been held up by opposition in the U.S. and Japan. The initiative focuses on tax payments made by internationally active companies in their home countries. Thus far, only tax authorities in the countries involved have been able to learn where companies are taxed and how much they pay. Washington and Tokyo are opposed to making such information public.

Tax experts in the German government have understanding for national peculiarities when it comes to such regulations. "It's like in your private life," says one. "Not everyone who climbs naked into the bathtub likes to expose themselves at a nudist colony."

Half-Hearted U.S.

At the moment, the transparency initiative isn't being pursued, simply because any attempt to force it through would be futile. If all the remaining countries were to agree on more extensive steps, Japan and the U.S. would simply withdraw from the current deal. The resulting damage would be greater than the additional value.

Another way to undercut tax havens is to compete with them. But this option is unrealistic for larger economies. For countries with hardly any industry like Malta and Cyprus, it may be worth it to attract foreign profits with low tax rates. But larger countries with established industrial bases would ultimately lose money. They would, after all, have to offer the lower tax rates for foreign companies to their domestic companies as well, meaning they would lose more revenue than they would gain.

Making the battle against tax loopholes even more difficult is the fact that the world's largest economy, the U.S., is rather half-hearted when it comes to fighting tax havens. The state of Delaware offers an anonymous home to hundreds of thousands of shell companies. The U.S. government - whether Democratic or Republican - has also for years been rather indulgent when it comes to multinationals dodging the taxman, despite the fact that it is the U.S. itself that is shortchanged by the tricks employed by Google, Apple, Amazon and co.

Tax revenues from American multinationals should be flowing into U.S. coffers, just as all profits from German automobile manufacturers, for example, are taxed in Germany. Global tax doctrine, after all, holds that taxes should be levied in the country where products are produced.

But for decades, U.S. tax law has maintained a loophole for American companies. They are allowed to park their intellectual property - in the form of patents, licenses or film rights, for example - with subsidiaries based overseas, which means that those subsidiaries are taxed in the countries where they are based. That is why Apple, as the new document leak indicates, didn't decide to pay taxes on its profits back home once an Irish loophole was closed. Instead, the company went searching for tax havens that might offer it a new home.

An Arduous Process

Why does the U.S. government allow such a thing? Why doesn't it close this long-known loophole? There are two reasons. Early on, the regulation was established to prevent the U.S. from losing money. After all, if companies don't need to tax their profits back home, they also aren't able to claim deductions when they lose money. But when the highly innovative companies ultimately proved profitable, the tax authorities didn't remove the loophole. The U.S. government has always seen it as a kind of export subsidy for domestic companies. For Washington, the influence of American companies abroad is more important than the loss of billions in tax revenue.

So is the fight against tax havens in vain? Not necessarily, but it is an arduous process that doesn't produce quick results.

Once coalition negotiations are complete, Merkel's new government will have little option than to continue doing what it can to block the flow of money to tax havens around the world. Some of those involved in those negotiation believe that Germany has a number of tools at its disposal for putting pressure on tax havens. One of those is Wolfgang Kubicki, the deputy head of the business-friendly Free Democrats (FDP) who could become Germany'snext finance minister. He even thinks that Berlin could solve some problems unilaterally.

Regardless of who takes over the finance portfolio, he or she should focus most efforts on convincing European Union partners to stop offering improper tax privileges. And convincing the U.S. of the same. Because just as with climate change, without the world's largest economy on board, little will change.

***

Share the link of this article with your facebook friendsFair Use Notice

This site contains copyrighted material the

use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright

owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance

understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic,

democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this

constitutes a 'fair use' of any such copyrighted material as provided for

in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C.

Section 107, the material on this site is

distributed without profit to those

who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information

for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml.

If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of

your own that go beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the

copyright owner.

|

|

|

|

||

|

||||||